This paper recounts the journey I took to explore how a prose writer draws inspiration from music and lyrics, as opposed to the traditional sources of written texts in books. Dancing in the Dark, my ‘prose album’ based on Bruce Springsteen’s record album Born to Run, appropriates and reworks Springsteen’s universal themes and female characters. It fleshes out untold stories suggested by Springsteen’s songs, amplifies the voice of a girl locked in the push-pull of staying safe in the house versus being free on the open road, and is juxtaposed to the traditional unquestioning masculine freedom quintessential in Springsteen’s lyrical terrain. Along the way in my writing process, I was accompanied by six Muses. Sylvia Plath, Dorothy Porter, Mary Fallon, Vicki Viidikas, Julia Kristeva and Marguerite Duras were my driving companions.

Keywords: music, writing, driving

—

Introduction

Music can be a channel for grace, words can be arranged to form poetry, love can exist and have a meaning. Things can be salvaged, the past

can be made to yield up something that is pure. ~ Helen Garner

I have always listened to music, listened intently, from the perspective of a writer, to the lyrics being sung, extracting the story being relayed, piecing together the narrative. I have early memories of listening to the records of folk musicians, kneeling in front of speakers, in a little posture of devotion, in my own melodic world. I was travelling, transported through song, feeling the rhythm, the beat through my body, and bringing to life the story in the theatre of my mind.

When I learnt to drive, this act of worship intensified, as it seemed to me that the act of driving, cocooned in my two-door red car with the music right up, was the most conducive environment to taking in a song. My body seated, yet moving forward, conscious of the road and the scenery flying past, awash in the pulsating pace of a driving beat, an unfurling lyrical narrative. Flying solo, these journeys felt like a different kind of travel to me. I would regret arriving at my destination. Like reading, I felt, for a time, tangled up in another world. I did not know who I would be when I got to the other end; the music still on my skin, the poetic words a serenade from the speakers, coursing through my mind, a haunting presence all day.

I would take the long way home, the window down, the volume up, the night unfolding just for me; street and traffic lights glowing off the side of my car, their streaking neon pleased me when I glanced in my side mirror, the wind in my hair. The soundtrack to my life the music I played in the car, against the backdrop of the night, somehow heightened my awareness of the narrative unfolding in the songs, looping around, never ending. Through this process, like reading, like writing, I was shifted; I would come home transformed. My driving became an important part of my methodology, in my ‘inspiration car’; like a musician might work out chords I would work out the stories in my head, they would percolate with my lunar auto roaming.

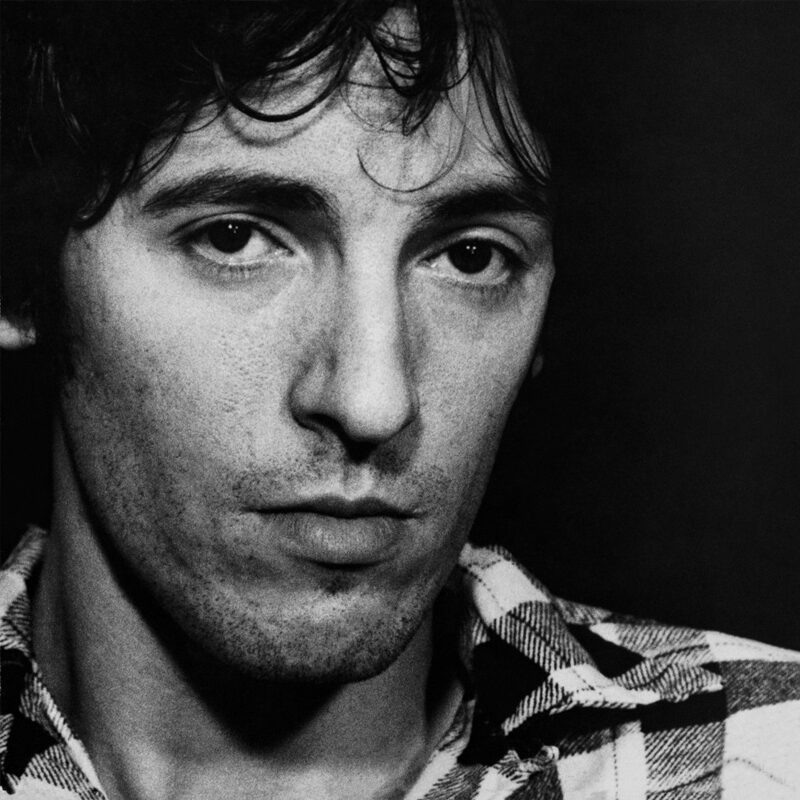

Haunted by Springsteen

I have known Bruce Springsteen for a long time. I learnt his music, his songs posed as stories, over the years through the radio. I had always been particularly fascinated by the story in ‘Dancing in the Dark’, by this man, wanting to shake off his body heavy with frustration like a threadbare overcoat, ‘sitting ‘round here trying to write this book’. A creature of the night, starved of passion, yet desperate to stay hungry for it. Radio on, bored, manic; he is offering himself, regardless of whether there is a ‘spark’, whether a fire is ignited by the interaction. His call is a warm shot in the dark, an attempt, even if no light is shed.

There will be dancing. Things will move.

I came upon a Born to Run special release box-set in a second-hand store in early 2011. I picked it up almost unconsciously. If I had thought deeply about the purchase, it would have seemed I was setting out on a path, driving down a road and I was not quite at the wheel. This purchase set in motion an organic process, fateful convergences and uncanny offerings, books, music, films all propelling me towards this writing. Soon he was all I listened to. I never tired of him. Bruce Springsteen became a constant male companion to this young solitary female trying to figure out what she wanted in life and in love and in stories. A presence I felt I had conjured somehow.

He began to haunt me.

I would hear his songs in the supermarket; I would discover an old much-loved song was actually a Springsteen cover. He appeared as the voice of reason to John Cusack’s character in High Fidelity, a more comedic version of how I perceived him. Reading Elizabeth Wurtzel’s memoir, Prozac Nation, there he was again; Wurtzel turned to him for solace during her long teenage years, lying in her bed, listening to him through her headphones. A kindred spirit:

Sometimes I lie in my … bed and listen to music for hours. Always Bruce Springsteen… I identify with him so completely that I start to wish I could be a boy in New Jersey… All that was left for me to do was shut down and enter the world of Bruce Springsteen, of music about people from where else, for people doing something else, that would just have to do, because for the moment, for me, there was nothing else. (Wurtzel 1994: 50-51)

When I watched the Born to Run documentary included in the box-set I was introduced to Springsteen at my exact age, talking about how, as a young artist, you have something huge inside you, yet you are unsure how to bring it out. Coupled with the songs of the album, a cast of characters emerged tantalised by ideas of escape and freedom, of cars and ‘suicide machines’, the possibility of love, spanning through the course of one fateful night:

Born to Run announced a change. It sounded old, and yet unlike anything you had heard before; it spoke with romance and longing and sharp pain for dreams of love; it befriended you and suddenly you weren’t alone… The characters were us, and they were both escaping from something and searching for something. (Masur 2009: 2-3)

As Masur suggests, like many listeners I felt Springsteen was speaking directly to me. There was also another layer of connection between us. I too, struggled with the idea of proving myself creatively. He treated the craft of songwriting like the craft of writing. I imagined this man first and foremost as a writer:

“I think you tend to write about things that you’re trying to sort out. I think you’re trying to write about things that you don’t understand and you wanna understand and so you’re workin’ on something to help you understand what that was all about … writing … comes out of that particular fire.” (Springsteen in Smith 2002: 149)

In Larry David Smith’s Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and American Song Springsteen described himself as a chronic observer, someone whose nature it was to stand back and watch the ways things interrelated (Smith 2009: 150): an artist with ‘a passion for the open road’ (Carman 2000: 196). His goal as a songwriter was to set out to create a good story, ‘“one where something is revealed, where something happens”’, to create characters that ‘“come to life”’, real, recognisable characters ‘“that could be you, that could be me in a certain circumstance”’ (Springsteen in Smith 2002: 155). Springsteen described his work as an ‘“ongoing novel”’. The care and construction he bestows on his characters is considered uncommon in popular music, for despite the use of song structures in his writing, his ‘attention to character development, scenic continuity, and narrative coherence’ is drawn extensively from fiction writing (Smith 2002: 155).

Springsteen would construct dense narratives and then embark upon a huge editing process, paring them down, stripping away the cliché yet keeping the imagery, the setting, the tension, the movement (Zimny 2005). He is in essence a storyteller. He regarded the songs in the album Born to Run like stories in a book, their themes and characters speaking to one another (Zimny 2005). The lyrics trace the lives of characters who could be anybody and everybody, and questions evolved from this writing process:

What do you do when your dreams come true?

What do you do if they don’t? (Zimny 2005)

But above all, the heartbeat of the album, of the young Springsteen’s existence, seemed to be captured in the refrain: I wanna know if love is real (Springsteen 1975).

“The primary questions I’d be writing about for the rest of my working life first took form in the songs on Born to Run (‘I want to know if love is real’). It was the album where I left behind my adolescent definitions of love and freedom. Born to Run was the dividing line.” (Springsteen 1998 in Masur 2009: 97)

Despite the vast differences in era, geography, artform and gender, I felt I was asking the same questions myself as a writer and as a person. Moving through days and nights behind the wheel, listening to Born to Run, I began to engage in an act of call and response. I began to wonder about the characters in these songs. They were all ‘“leaving something and… going somewhere they don’t know where they’re going… trying to find somebody to accompany them… [to] love or care about”’ (Springsteen in Masur 2009: 112). In particular, the women. I was intrigued especially with Wendy, from the title song. Wendy Darling, the girl from a collective childhood imagination, appropriated as the star of Springsteen’s epic love song, grown up and yearning for love, for escape. From Peter Pan and those lost boys. This idea resonated loudly. I was a Disney child reared on commercial notions of fairytale, of love and romance, which it seemed I was only just beginning to see through.

Springsteen’s traditional narrative voice and themes, the wallowing through the mundane, as he explores the small moments in the lives of ordinary people, mythologising the commonplace, moving towards grandeur in daily living, mobility, and the beauty inherent in simplicity; these themes all influence my writing. The power of a moment’s minutiae transformed into poetry. Buffed banalities, a little touch up and a little paint.

While for the most part Springsteen’s songs are dominated by his ultra masculine presence, I perceived an inherent sympathy in his writing towards women and his female characters. I wanted to know more about these women, know their stories, not just where they began and ended within the songs. I wanted to respond to his work in reverse, so to speak, flesh out the characters from the bones presented in the lyrics and extract and expand upon their slim representations. I began to imagine myself as the women in these songs, enmeshed in love stories with difficult men, yearning for escape or redemption:

Writers and artists create little worlds and control them. You do that well enough, and you begin to believe you can live in one of them. But the real world doesn’t work that way. Love levels the playing field, you can’t predict its outcome, and the same rules apply to all. (Springsteen 1998: 218)

I felt that, to some degree, I had met these men, had had these feelings. I had my own cast of lost boys and perhaps needed to sublimate, as a mode of catharsis, to mould tragic love affairs into stories, pour my own life into the work. This project would be a lyrical assemblage, with Springsteen as the voice of meditation. Appropriating Springsteen, his image, I would take his lyrical narratives and merge them with my stories and the narrative would unfurl from the perspective of one specific female narrator – Wendy – and as she took to the road, to escape, to forget, to find herself, I would loosen my edges.

My prose album

Dancing in the Dark, my ‘prose album’, is a collection of lyrical short stories and prose poems infused with the creative enigma of Bruce Springsteen and appropriated themes from his songs. Dancing in the Dark is a narrative from the perspective of the central character Wendy. Wendy Darling (appropriated by Springsteen himself from Peter Pan in his song ‘Born to Run’) is in my work a woman finding her way through life and love. Wendy is a persona I adopted to relay my own experiences. Our stories are interwoven as she embarks on a road trip, shedding old skins and exploring alternative identities, as I did when writing. Blending elements of creative nonfiction and appropriated Springsteen thematics, my stories and poems emerge dealing with notions of dreams, escape, freedom, sex and doomed love, from the alternative perspective of the observing female, rather than the active male narrator in a typical Springsteen song.

I intended to create a cinematic style in the telling of the story. I pictured Wendy very clearly in my mind: an empowered, yet fragile femme fatale, as she would look on a big silver screen, taking off through the night, fleeing old scenes, warding off the ghosts of old loves. As Springsteen first came to me in my car, his sensual, gruff voice in an interview following a song, it made sense that he would come to Wendy in this form too, at the beginning of the creative piece. From Wendy’s central perspective the other stories unfold, through her, and through the personas of the chorus of women, Springsteen’s women, incanted at the beginning of the piece. The operating idea being that Wendy as we see her here represents every woman – every story is being told either by or through her. Included in the narrative are ten Springsteen tracks specifically extended as prose poems; my goal was to animate the former lyrics into miniature moving pictures of the former snapshots. The interludes included in the creative text act as a more specific conjuring of the Springsteen enigma, the dreams, the fantasy of who he might be as a man, who Wendy wants him to be, or who I imagine him to be. I created a narrative saturated with Springsteen’s aura and oeuvre, amplifying the female presence in his tracks, providing her with agency and setting her free on the open road.

Come, walk with me out on the wire. This gun’s for hire…

interlude…the other man I romanticised over the summer A weeknight, party lights; uneven ground. ‘Do you think I mould men into Springsteen?’ ‘No; I think you reject men when they don’t match up to your Springsteen ideal.’ ‘I think we just view intimacy differently.’ ‘Yes. You’re more Secret Garden, whereas I’m more of an amusement park, with a rollercoaster, and a haunted house. “Born to Run” meets “Tunnel of Love”.’

Laughter, only from him. This was a sign. I took to the road. (Fraser 2012: 9)

Because the world of rock and roll, and the rock and roll album, seem so obviously drenched in masculinity, the working idea for my writing was to challenge the masculine by drawing out the female narratives in Springsteen’s lyrics. I thought of presenting my work as a kind of ‘concept album’. I would take significant Springsteen songs and expand upon them, draw them out into lyrical prose poems. I would then infuse Springsteen’s presence into longer short stories, blending the created persona of Wendy with my own life, slivers of creative semi-fiction. In Springsteen’s work, and particularly the Darkness on the Edge of Town album, I identified a list of defining tropes: the nexus of escape/driving/racing/riding; the colour red; darkness and night; blood and love. I blended them into my own work – stories which would revolve around love and its various forms – a chaotic space part-Disney, part-spooky fairytale, inspired by the idea of the appropriated Wendy character, now a woman, a sexual creature, plucked from Neverland and the world of Peter Pan, into Springsteen’s world in Born To Run.

In writing my work I toyed also with the idea of the artist’s persona. As a writer and in day-to-day life, I often feel like a pastiche; taking qualities from other writers and other people I like and incorporating them into my persona, as if I might be a living work in progress, an assemblage; pondering on the different lives I could have lived; I often want to be able to split myself into pieces so I can have as many experiences as possible. I flirted with the idea that I’ve conjured various events or people into my conscious life, just as I had done with the Springsteen visitations in my car. Springsteen was speaking to me, we were both wondering how to prove ourselves artistically, how to love, who to love, what to hope for. I would transpose his blue-collar Jersey grind and tropes into my stories and poems. Like Springsteen’s writing, I wanted to craft ‘twisted autobiographies’ uncovering ‘an inner life and unresolved feelings that I had carried inside me for a long time’ (Springsteen 1998: 190). I had found a place for my stories to go, to breathe.

Fascinated by what seemed to be the freedom inherent in masculinity I juxtaposed this with the modern push-and-pull of the girl in the car versus the girl in the house, notably in my story ‘Restless Rituals; A Dance In The Dark’, answering back with my own lovelorn tale, warmed by summer and encroached upon by the night.Passion, danger, ecstasy, despair. I wanted to tell the missing side of the story, the girl entranced by the ‘Big Three [rock and roll] themes: sex, escape and the redeeming power of music’ (Sandford 1999: 101). In doing so, I would take ownership of the themes, colour them with my own sense of self and story. I would enable the music to be woven into the words on the page, perceived visually instead of aurally. All of it storytelling, regardless of mode of delivery, regardless of vehicle, transferring imagined experience into art:

Springsteen transferred what he didn’t get to experience outdoors in the summer of 1975… into the lyrics he wrote indoors… The line in ‘Thunder Road’ about wasting “your summer praying in vain/For a saviour to rise from these streets”… For many, Springsteen himself would be that saviour, but both he and the narrator of ‘Thunder Road’ reject that role for the summer simplicity of rolling down the window and letting the wind blow back your hair. (Masur 2009: 115)

And so I wrote:

Wendy… Wendy… Wendy… Wendy Darling, blew in from Neverland, to grit your grease, underneath her fingernails.

You just turn on the engine and let your mind open. Let it wander. How well driving lends itself to roaming thoughts. Cruise control. Highway driving; eyes fixed on one point ahead, the tail lights of the car in front. Like reading a book, you don’t study what is physically before you, the printed words. You see beyond it. Through it.

Hitting all the red lights before the exit. If only Wendy hadn’t stopped to look in the mirror, turned back to undo an extra button on her blouse. Tight blue jeans; red sneakers. Form and function. Put your makeup on, fix your hair up pretty. War paint, lipstick a little smudged, mascara flaked on her cheekbones like gunpowder. A little touch up and a little paint. Eyes as clear as a high note. In the slow pan of shifting streetlight, a clue is revealed, a red tattoo in the crook of her arm. A secret space; two hearts, intertwined. (Fraser 2012: 1)

The Muses

Accompanying me on my musical road journeys, riding shotgun beside the conjured presence of Springsteen, were my own chorus of women, my own muses. Four poets, in the form of books sliding across my passenger seat. Plath, Porter, Fallon and Viidikas. My reading over a summer tied into the project, what I was writing and who I was becoming, in a strange serendipity.

Though written by Ted Hughes, the poems in Birthday Letters (1998) are primarily about, and saturated with the voice of Sylvia Plath, whose presence in the poems Hughes conjures. The idea of conjuring has manifested not only in my relationship to Springsteen, but in the accompanying events depicted in my creative work and the avenues that have driven my research paths. Hughes mentions Plath’s preoccupation with ‘conjuring’ in several poems in the collection, and the idea is also touched on in the 2003 biopic Sylvia. From what I understand, she believed, and feared, that she so thoroughly crafted situations in her mind, in full-blown anxiety-ridden detail, that she forced the events to occur in real life. She made things happen. This notion intrigued me and enhanced the movement of my project. Hughes elaborates here in ‘18 Rugby Street’:

Happy to be martyred for folly I invoked you, bribing Fate to produce you. Were you conjuring me? I had no idea How I was becoming necessary, Or what emergency surgery Fate would make

Of my casual self-service. (Hughes 1998: 22)

The concept of the ‘conjurer’, this strange, supernatural experience of Plath’s, is relevant in the ways in which I have conjured Springsteen both consciously and organically. His conjured presence also seems to mirror the thematic base of his songs: escape, cars, movement; in the way he came to me and to my character, in her car at night through the speakers, eerily speaking to personal events and experiences through the women and relationships depicted in his narrative.

I go. Pulled, seduced by a different force. Another man. He comes to me in the car, conjured, his voice moves with the night, in and out, the window down, my hair caressed by the wind and his voice in my ear. He is a companion, his presence feels like bliss. Engaged in a dance. Light and shade. Nights when I struggle to keep my eyes open, driving his voice grows louder, as the music does in my body, moving to the beat. (Fraser 2012: 9)

The poems of Dorothy Porter also influenced the trajectory of my work. I discovered in her essay On Passion (2010) ideas specific to my thinking and research. My prose album took the shape of an extended love poem of sorts; certainly the thematic search for love is its heartbeat. Porter’s dismissal of the notion that the art of poetry is dead, that it doesn’t appeal to or have any place in the lives of modern people, is hugely appealing to me. She says that the love song is the most enduring subject in music, and what is a love song but a poem? Like Wurtzel in Prozac Nation, pop and rock and roll music provided solace to Porter from a young age and also influenced her writing practice. Rejecting the idea of the poet cloistered away in silent reverie, Porter points out:

I … have written virtually all my poems to rock riffs and rhythm – the catchier, the darker, the louder, the gutsier the better. Whatever works. Music has been my magic. I have no idea how and why it works on my heart, imagination and pen the way it does. (Porter 2010: 26-27)

She describes this symbiotic process as injecting her psychic veins with music, mentioning Springsteen, and his ‘blistering “She’s The One”’, as offering the kind of ‘dark energy’ she wanted to ‘tap into and flood through [her] poetry’ (Porter 2010: 28-32). The imagery attached to the description of her methodology was hugely seductive to me, relating directly to how I perceive music and how it influences my writing. Porter’s ideas echo my own belief that music and lyrics speak to writing and to poetry; that these narratives of love unrequited, doomed or lost, feed off and blend into one another in an intertextual play.

Springsteen artefacts, an anthropological dig. A dream of rifling deep down inside his dresser drawer, of peeking under his pillow. Helping myself to sandwiches and beer from his rider, a slow awesome exploration of his dressing room. Notebooks, suitcases, a stone pony figurine. Like the intimacy of artefacts strewn across a stranger’s bedroom floor, each commonplace object is imbued with significance, magic even, in the dreamer’s mind (devils and dust). I open your closet and inhale your babe-like scent. (Fraser 2012: 20)

The third muse, Mary Fallon, influenced me in terms of the experimental form, structure and content present in her feminist narrative, Working Hot (2000). The book chronicles the lives of a cast of sexually-liberated women in a chorus of voices. Their poetic dialogue depicts them and their tempestuous exploration of life, their imperfect and tumultuous love affairs, flying in the face of the stereotypical feminine passivity often found in love stories. These women are empowered, highly mobile, sexually empowered; their lives sprawl through a narrative displayed lyrically and influenced by operatic frameworks, in the form of an extended prose poem. Fallon constructs a literary world that brings the impassioned female voice to the fore. This text was a radical emblem of what I sought to do with my Dancing in the Dark; it inspired me to engage freely in an assemblaic structure. As depicted here, Fallon weaves her tale through a musical scene structure:

An Opera for Three Voices and a Choir of Five Hundred

SETS AND MUSIC

FOR SCENES ONE TO FIVE The stage is gloss white and empty except for the three singers. The stage and the singers are always bathed in light from projected slides of women’s bodies, parts of women’s bodies, molecular structures and cells of skin, hair, nails, vaginal flesh, eyeball tissue. The music is amplified sounds of the body functioning, i.e., heart beat, swallowing, stomach digestion, etc.SCENE ONE

slides of bodies, close-ups of palm flesh, underneath the feet, beside the mouth, e.t.c., the sound of fabric being ripped…

SINGERS

INSIDE INFORMATION in white

E.C.R. SAIDTHANDONE in red

ARCHANGEL MADEMOISELLE MONTGOLFIER in gold and a five-hundred-strong choir

[Choir chants in the darkness before the opera begins] (Fallon 2000: 119)

And I wrote:

- 3 pairs of blue jeans

- 1 black leather jacket

- 2 red bandanas

- 5 plaid flannelette shirts

- 7 singlets (navy, white, red)

- 55 t-shirts (black, white, grey)

- 1 black suit

- 5 dress shirts

- 1 purple paisley shirt (!)

- 3 vests (denim, black, grey)

- Belts, various hats, black motorcycle boots, sneakers…

And then…

Amidst the miscellanea, amps, effects pedals, harmonicas, tambourines, microphones, picks, cables: the plethora of Fenders and Gibsons sparkling like jewels, tuned and strung and ready to rock and roll. (Fraser 2012: 20)

The work of Australian poet Vicki Viidikas, a bohemian wanderer and observer, also influenced my project. Viidikas lived as she wrote. She spoke of writing from direct emotional experiences, with the belief that true value in writing has its roots in raw personal experience. ‘I am interested in personal truths for the poet’, she says in a 1975 interview with Vogue (Alizadeh 2010). Writing for her was like ‘drawing the spirit out’ of herself. These beliefs, her poetry and her methodology fed into my contemplation of my work and how I was writing about Springsteen and his body of work. Her poem ‘They Always Come’ (1973) is rich and raw Viidikas. While expressed more aggressively than the intimate tone of Dancing in the Dark, she too writes about loss of innocence and challenging notions of femininity. Viidikas shows what it’s like for a woman to live more freely, as a man would, themes and ideas echoed strongly in my work:

When they have taken away the childish laughter and dog-eared books, peeled off the last mush embrace, given the girl

her lipsticks, hair rinses and pills

When they have poured back the drinks as long as empty deserts, returned the spurs to the one-night stands, taken off the overcoat

and riddled her bed with song

They’ll find a mirror smothered in lips a vacant room with stale cigar ash, an unpaid bill for a Turkish masseur,

a woman’s glove by a handsome typewriter

They’ll see charleston dresses of the mind with their fringes running like blood, a list of men’s names from childhood to eternity, they’ll dig the very fluff from the floorboards,

examine the stains on the manuscripts

Which drug did she take? Which pain did she prefer? What does the lady offer

behind the words, behind the words?

Their criteria will be: so long as she’s dead we may

sabotage and rape (Viidikas 2012: 112)

And I wrote:

Sometimes when the light is right he comes around. A touch before night becomes day and she lets him inside. He woos just with his way. Sweating over the craft of the kiss. She lets him inside her mouth. He doesn’t regard her as a riddle, a blind spot on a well travelled road. She is new, he is learning her, willingly wading right in over his head, submerged in the flotsam, the detritus, the distant flicker way above of gasoline rainbows streaked across the surface. (Fraser 2012: 23)

The most valuable working concept for my writing, and allowing the writer to draw from and appropriate from lyrics, has been the idea of intertextuality, read mainly through the theory of Julia Kristeva. Her belief that creative works are drawn from pre-existing texts rather than one author – that ‘texts’ are permutations, that they intersect – is a logical working and philosophical definition of written work. Kristeva defines this process of creation as a text being composed of two axes: the horizontal one connecting author and reader, and the vertical, which connects the text to other texts (Kristeva 1980: 69). Intertextuality allows a ‘text’, a term Kristeva applies to musical ‘texts’ and other art forms, to exist in societal continuum, suggesting that a text is not a standalone product, that it doesn’t possess a unified meaning of its own. The text for Kristeva is always in a state of production, always unfinished, thus allowing the reader their own individual, justified interpretation. There is a constant dialogue occurring between texts, between readers: ‘any text is constructed as a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another’ (Kristeva 1980: 66).

Kristeva’s concept of intertextuality operates within my writing process in a twofold way. Firstly, it illustrates how listeners of Springsteen’s music relate to his songs as lyrical narratives, because they can make additions to and extend upon the stories being told to them. Empathy is evoked, the listeners are moved through what they bring of their own experience (their personal ‘texts’) to the songs. Secondly, the concept of intertextuality allows me to appropriate Springsteen’s lyrical narratives, to refashion and redesign them to suit the trajectory of my creative work, to adapt and transform his lyrics to suit another fictional world, another author. His stories are, in my Dancing in the Dark, in a process of becoming the stories I want to tell.

A Californian summer sojourn. I wonder who else has breathed this air, those that live lives bigger than mine, amplified by sound, magnified by screen. We drive and you take over the airwaves. You’re new at my side but there’s a sense of an ending right from the start. I keep my headphones on, creating my own soundtrack. I can hear the heat, taste the colours, blue, white, red, undulating through the air, coming in thick through the window. Tremolo. (Fraser 2012: 35)

I wanted to demonstrate the intertextual relationship occurring between music and narrative, with the view that there is no one way to interpret the works of one author, one artist. Each listener or reader brings their own meaning to the text. The readers of my creative work join the dance; become part of and aware of the intertextual play. While Kristeva suggests this process is always at work in textual comprehension, the visibility of these connections in Dancing in the Dark is obvious, deliberate and part of the structural logic and aesthetic satisfaction of the narrative. One text is never closed off from another; the concept of intertextuality allows for both my connectedness to Springsteen and to readers of my writing, opening up new associations in my thinking and research, everything speaks to everything else. Orr points out: ‘For Kristeva, text of any kind is not a vehicle of information (“the that which it signifies”), but so many forms of reflexive and hence “poetic” language … in cooperation’ (Orr 2003: 30). Text is never just one static thing, rather it is moving, growing and being brought to life by the reader in all of its cooperative parts; a text does not merely utilise a prior text, but transforms it. With Kristeva in mind, I wrote:

The night is a balm for listlessness, restless thoughts; craving. The man in the shadows. A gun for hire. No more than that. He clouds her dreams like blood in water. She’s the siren at the side of the ship. Though sometimes she dances, with herself, as she moves around her apartment, till she sweats, indulges the smoking gun. No more than that. She can’t discern his features; it’s better that way. Radio’s grain seeping through the colour of the night. In her bedroom, watching herself in the mirror, the conjured figure behind her, taking in her face, her hair, her clothes. Each article a kindling. Stoking him. (Fraser 2012: 27)

The theorists I have been influenced by develop in their own ways the understanding that a source is never truly singular; in terms of culture every item, icon or ‘text’ carries with it a complex set of associations, which form or make possible a unique and continuous meaning in the mind of the reader. Writer Marguerite Duras once pondered: ‘Perhaps I am an echo-chamber’ (Duras 1974: 218). This notion sits well with me, as with Duras’ prompting I am able to visualise myself, my body and my work as a kind of echo chamber that takes in Springsteen’s music and narratives and both transforms and relays them. So I wrote:

To get to your room I had to walk down the dark hall of your parent’s house. Pictures of your eclectic heroes on the walls: rock stars, Escher’s hands, a topless girl. Empty exotic beer bottles on a shelf. A single bed with plain blue sheets where you drew first blood. Victor’s feast of chocolate bars and a cup of black instant coffee in a cartoon mug. When we kissed I could hear my heart in my chest. You told me to close my eyes. (Fraser 2012: 38)

My body, my writing, is the point where research, thinking and lived experience converge; there is symphony. The notion that everything feeds back, that there is an enduring dialogue between texts, seems inherently musical; there is a chorus, and a refrain.

“Over … years you internalise your craft, and the mechanics of storytelling becomes like a second language that you speak without thinking, like a second skin that you feel with.” (Springsteen in Kirkpatrick 2007: xii)

Conclusion

The purity of human expression and experience is not confined to

guitars, to tubes, to turntables, to microchips. There is no

right way, no pure way, of doing. There is just doing.– Bruce Springsteen

Appropriating Springsteen’s lyrical narratives in my prose work Dancing in the Dark proved a fluid process in connecting literary narrative from the page to lyrical narrative in music. I sought to explore an innovative mode of writing, of storytelling, through understandings of poets, writers, lyricists and theorists, and through conjuring Springsteen as an artist and a man. I feel I achieved a unique exploration of Springsteen’s music and lyrics, the enduring impact of his status as a ‘rock n roll’ and pop culture enigma, adapting each aspect of his ‘story’ to suit my own ‘twisted autobiographies’. My writing modified and responded to his lyrical narratives, overlaying and threading them through fictional or real life-inspired personas in a collection of interconnecting original short stories and prose poems. Using music to guide my written work proved to be a successful journey for me.

Rising sun streaking across her Aviators like gasoline rainbows. Wind in her hair, wild heart, open skies. The pages of the scrapbook flutter, empty. Their contents now ghosts on the highway.

She presses ‘next’ on the luminous music dial just before the close of each song – six string possibility, endless musical combinations – if songs don’t have an ending, they play on and on in your mind forever.

Broken white lines as far as the eye can see.

Pedal to the floor; she’s crossed the state line.

“I wanna die with you Wendy on the streets tonight in an everlasting kiss.” (Fraser 2012: 66)

—

© Zoe Fraser

Zoe Fraser is currently a PhD candidate at Griffith University on the Gold Coast.

Springsteen, Six Muses And Me: Music And The Writing Process

by Zoe Fraser ~ First published by Text Journal

—

Works Cited

Alizadeh, A 2010 ‘Vicki Viidikas Rediscovered: Ali Alizadeh Interviews Barry Scott’, Cordite Poetry Review, http://cordite.org.au/interviews/barry-scott/ [accessed 17 May 2012] return to text

Carman, BK 2000 A Race of Singers, Whitman’s Working-Class Hero from Guthrie to Springsteen, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC return to text

Duras, M 1974 Les Parleurs, French & European Publications, New York return to text

Fallon, KM 2000 Working Hot, Random House, Sydney return to text

Fraser, Z 2012 Dancing in the Dark, Unpublished Honours Submission, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Qld return to text

Hughes, T 1998 Birthday Letters, Faber, London return to text

Kirkpatrick, R 2007 The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT return to text

Kristeva, J 1980 Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, Columbia University Press, New York return to text

Masur, LP 2009 Runaway Dream, Born to Run and Bruce Springsteen’s American Vision, Bloomsbury Press, New York return to text

Orr, M 2003 Intertextuality, Debates and Contexts, Polity Press, Cambridge return to text

Porter, D 2010 On Passion, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne return to text

Sandford, C 1999 Springsteen Point Blank, Little, Brown and Company, London return to text

Smith, LD 2002 Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and American Song, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT return to text

Springsteen, B 1975 ‘Born to Run’ on Born to Run, Columbia Records, New York return to text

Springsteen, B 1998 Songs, Avon Books, New York return to text

Viidikas, V 2010 New And Rediscovered, Transit Lounge, Yarraville, Vic return to text

Wurtzel, E 1994 Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America, Riverhead Books, New York return to text

Zimny, T 2005 Wings for Wheels: The Making of ‘Born to Run’, Documentary, Thrill Hill Productions, New Jersey return to text

—